Artificial Intelligence is developing at an unprecedented rate, triggering debates as to whether it will be able to replace all industries, including the creative ones. I recently posted the following thought:

AI does not represent a threat to the creative industries. It will help with service-based jobs, end of story. No one wants AI art, AI movies, AI scripts, AI literature. If you believe AI will replace creativity, you don’t understand what it means to be human.

In response, Geoffrey Miller, an evolutionary biologist, wrote:

Catastrophically naive. If you don't think AI threatens people in creative industries, you don't understand AI, or markets, or careers, or culture.

On the contrary, I argue AI can unleash humanity’s creative potential.

AI lacks ingenuity. Teleologically speaking, we designed machines, so those machines cannot create an original design without being told what to do. They can only execute orders; they cannot invent. This argument is a straightforward one for those who seek to question the value of technological development.

However, even the best argument in defense of AI threatening the creative industries falls short. It rests on the assumption that machines are more efficient than us. In this regard, innovative industries that rely on technology, like graphic design, may struggle. But handmade work will continue to grow and thrive. While AI defenders are correct in arguing that machines offer in a few seconds what we may take hours, days, weeks, years, or even decades to accomplish and are precise in ways we cannot hope to be, they’re missing the mark. Value doesn’t rest on efficiency. You can instruct AI to create any image by following the traces of famous painting masters of the past, for example. It will do so instantly. But AI lacks the uniqueness inherent in our humanity.

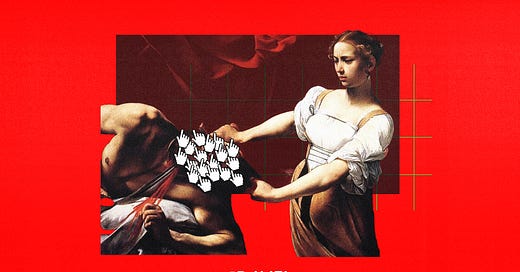

Compare an AI-generated image to a handmade, original painting by Caravaggio. One was made in a few seconds, the other through effort, obsession, even sweat, tears, and blood (Caravaggio was infamously accused of murder and was often living as a fugitive, escaping persecution for his crime). At a gut level, does the AI-created art feel as full of life as a Caravaggio painting? Perhaps we can’t put our finger on why, but it’s clear to anyone who observes closely the different feelings the painting by Caravaggio evokes. Emotions transpire through our work. When we are spectators of great art, we sense a wonder that cannot be articulated through reason—it speaks to our most primitive understanding of what it means to be human and attempt to create a glimpse of the divine through our work.

Perhaps some cannot make this distinction, as AI work can become virtually undistinguishable from our work. But we’ve seen this development before with industrial production, yet we developed verification systems to understand whether one was original or a mere copy produced by a machine. We are inventing similar screening methods today with AI, where we can copy and paste texts and detect whether a person wrote them. We create these authentication systems because we value human work to the highest degree.

A parallel can be drawn in therapeutic developments. Some people claim that “trauma-dumping” ChatGPT with your life story offers a more objective analysis of your psyche than a licensed therapist. Likewise, many are starting to use AI to help them manage relationships more effectively. AI is capable of offering us psychological insight, and withstanding our insecurities and grievances in ways an individual may not be able to without biases and assumptions.

Reaching out to AI for life advice can be calming, to some, because it is designed to generate positivity, avoiding the criticisms and imperfections that make individuals so uniquely flawed and, often, so unbearable to us. Still, the chatbot can help you manage those relationships, but not replace them. AI may give you advice free from judgment or awkwardness, but a friend will give you the warmth and connection a machine lacks—the same way an object made by us carries that sensation through our creation, and its imperfections only add value to the work of art. We desire that same connection, even to the simplest objects around us.

A similar panic occurred during the Industrial Revolution. Suddenly, automated processes could mass-produce and manufacture goods in enormous quantities. This development saved time and resources. The items produced were identical in both appearance and function in a way that we could not replicate with the same expediency and detail. It also made them cheaper, and it made us, in many ways, materially richer.

The Luddites were concerned with how machines would replace their labor. However, the value of artisanship only increased during the Industrial Revolution because it became rarer. Demand was higher, and supply was lower, making prices skyrocket and artisans more prosperous. Only the elite classes could afford handmade goods when they were once the norm for every economic class of society. A valuable criticism of the rise of industry and technology is the lowering of the quality of goods for the masses. Quality has been sacrificed at the altar of quantity. Why? Because there is nothing impressive about a machine creating a great work of art beyond its technical capacity. The ability for us to strive, fail, and strive again, however, does impress us.

This is not a mere conjecture; the value of handmade work in the market speaks to this reality. High-fashion is comprised entirely of handcrafted products, and it is precisely the fact that they were made by artisans and craftsmen, that they possess imperfections created through the experience of effort and struggle, that they become more beautiful to the human eye. These imperfections are so revered that when you buy high-fashion items, it states, “Imperfections on this product are testament to its uniqueness as a handcraft.”

The greatest Renaissance figurative artists had a unique style that distinguished them from other painters. Their creations were awe-inspiring not because they were perfect, but because they sought to achieve excellence. Excellence means attempting to reach the perfect but failing. It implies seeking to exalt the divine in us, a divinity that has created us as imperfect.

The error in the idea that AI will replace art lies in the belief that we desire perfection more than authenticity. Machines are superior to us in skill, yet skill does not contain the ingenuity of creation, the authenticity of thought or the pain in deliberation. Skill is execution: it is machine-like. There are painters with excellent skill but no invention and, furthermore, no originality in creation. Likewise, there are painters with inferior skill but a genius invention and a unique technique in creation, and their work can elicit feelings in their spectators because it reflects the character of their emotions. This is what distinguishes a painter from an artist. Likewise, it is what distinguishes a machine from us.

What makes us impressively human is technique rather than skill. I once completed a workshop with a painter named Vincent Desiderio, who said skill isn’t so interesting, but technique is. Technique involves trusting ourselves, and trying and falling short to bring our own, unique idea and essence to life. When we see it, we instinctively appreciate its courage. Technique can be copied with skill, but it cannot be created.

An imperfect painting made by a human is superior to a perfect painting made by a machine. This is because the former was made by an individual that cannot be replicated and in a space and time that will no longer exist. The latter was created by a machine that can be reproduced, and which can create millions of the same copies on end. Scarcity creates value, so does originality. We are precious precisely because no one will exist like us again, or in the same temporal reality as now.

AI can make life easier for us. The Industrial Revolution replaced much of our manufacturing labor, including the most tedious kind, but AI can bring us a step further by replacing even service-based labor. It can provide us with the most practical advice, going so far as potentially replacing industries like medicine as we know it. But even the practice of surgeon is that of an artist. Would you trust a machine to lay its hands on you, to cut your flesh open? For all the imperfections a surgeon carries, paradoxically, they allow that surgeon to see yours in their complexity and fix them.

AI can allow us to become geniuses in our own right, using our talents as God intended. As our repetitive labor might be replaced, we may become free to all become poets, artists, painters, designers, novelists and philosophers, because these are the modes of being no machine will be able to imitate. That is because we live, while machines merely exist. Ironically, this was Karl Marx’s prophecy for the natural evolution of a hyper-capitalist society.

Nature makes us feel connected to the divine because God created the natural world, in the same way handmade creations make us feel connected to our humanity because humans made them. Just as we cannot replicate Godly inventions, machines cannot compete with our creations.

Alessandra Bocchi is the founder of Alata Magazine and Rivista Alata.

Exactly.

Your aunt's paint-by-numbers Starry Night might be an exact replica of Van Gogh's work. Who cares about your aunt's painting? Nobody except her. (No offence to our hypothetical aunt.)

The same with a Robot Olympics. SprintGPT might one day blast the 100 metres sprint in 2.9 seconds. Nobody will care. We seek art and excellence because we are a limited and flawed species. With respect, those who claim AI will replace art, do not understand art. The intentionality is integral; the result is, at very best, secondary.

AI is a great tool. Our crisis-sodden times fetishise the future. AI is not God or a saviour. Neither are any of the other isms and illities many claim will save us/lead us to utopia/make everything better.

Why would we seek to save labor, in mechanical terms borrowed from industry, in the only category of human experience in which the labor (and the hiding of labor) IS the essential value? How can a machine express Sprezzatura? It’s a laughable proposition.